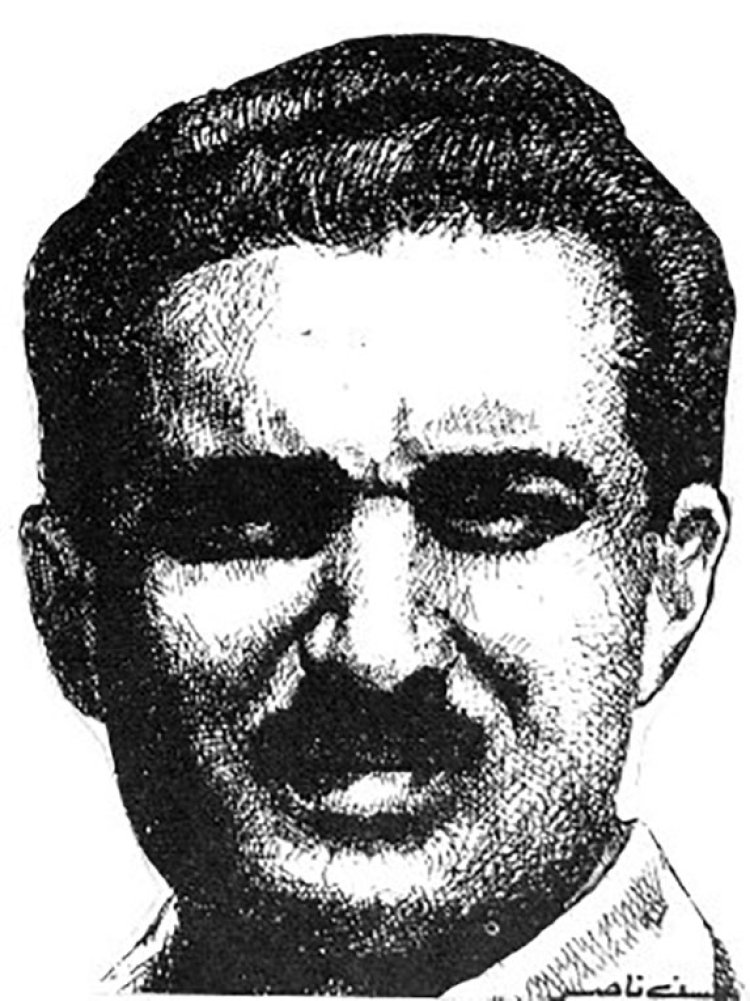

Hassan Nasir - A Democracy’s Martyr but His Legacy Still Shines Bright

In 1960, Hassan Nasir was arrested and transferred to detention center Lahore Shahi Qila, where he was physically tortured and martyred. The government claimed that Hasan had committed suicide on 13 November but his mother did not acknowledge that the exhumed body was that of her son, when the body was recovered on 20 December.

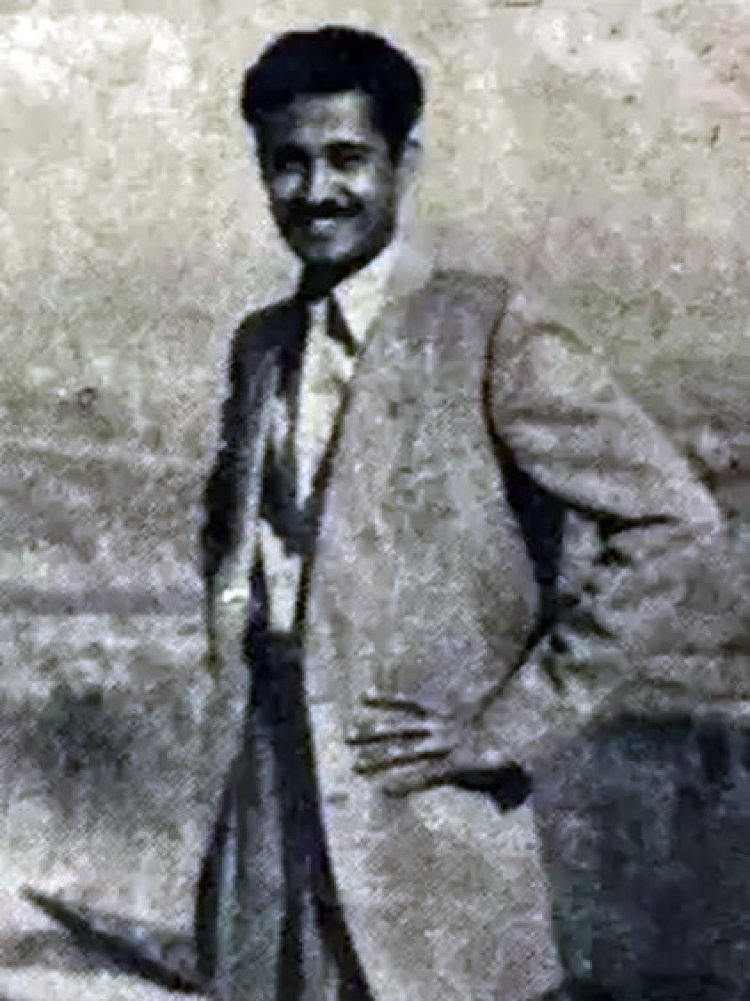

Syed Hassan Nasir (1928-1960) was born in 1January, 1928 to an upper-class family in Hyderabad, Deccan. The great grandson of Nawab Mohsin ul Mulk, Hasan Nasir became a dedicated follower of communism while he was studying at Cambridge. A dedicated social worker immerse in the workers’ struggle, his life was cut short at the young age of 32 when he died after being tortured brutally in Lahore Fort on November 13, 1960.

Hasan Nasir was one of several communists who migrated to Pakistan at the time of Partition, including Sajjad Zaheer, Daniyal Latifi and others. He came to live in Karachi and joined the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP). The CP was banned in the wake of the 1951 Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case, and Nasir joined the National Awami Party (NAP) in 1957, which was the only opposition party to the growing power of the military and its alliance with the United States of America. Nasir was elected to the central working committee and became the party’s secretary general for Karachi. In his stewardship, the office was less a hub of the NAP and its politicians, and more that of labour and students unions.

Hasan Nasir was a young leader in the struggle on the issues of workers and peasants. He took part in the "movement of landless peasants of Sindh".

He came from an upper-class and rich family of united India but he had voluntarily chosen a life of poverty, driven purely by a passion for the communist struggle.

The Pakistani leadership was getting more and more embroiled in its alliance with the United States and was becoming a client state, ready to be used against the Soviet Union at that time. The state began to crack down on all communist and left-leaning politicians and intellectuals. Hasan Nisar was in and out of prison many times and was finally exiled from Pakistan in 1954 for one year. He returned to his parents’ home in Hyderabad India but his heart was in the bastis of Karachi. He returned from exile and continued his struggle.

General Ayub Khan took power with martial law in 1958. The newly-empowered military and civilian bureaucracy began to suppress all democratic opposition with special emphasis on communists.

Every communist were harassed like as agents of the Soviet Union and branded traitors. As recounted by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, when the renowned lawyer Manzur Qadir brought up the case of the detention of Major Ishaq, in a cabinet meeting, Ayub retorted, “Oh, that bloody communist! I think he should be executed”.

The Lahore Fort, magnificent and awe inspiring though it is, was a detention center in the dungeon, for decades, right through to the Zia era.

The Punjab Police CID had a detention center in the dungeons and other state intelligence services routinely tortured political activists and their like in those holding cells, their screams resonating in other cells, in complete isolation from the rest of the world.

Hasan Nasir was brought to one such cell on September 13, 1960 after being arrested on August 2, under the Security of Pakistan Act, 1952, on the orders of the Administrator of Karachi. Interrogation was complete by October 24 and he was to be sent back to Karachi by October 29.

But he never reached to Karachi and was murdered in cell number 13 of the Fort. It is said that Hasan Nasir’s torture unto death was ordered by the then Inspector General of Police, Khan Qurban Ali Khan.

Major Ishaq filed a petition for extradition of Hasan Nasir on 22 November 1960, on which day the government claimed that Hasan had committed suicide on 13 November and his mother Zahra Alamdar Hussein did not accept it when the body was recovered on 20 December.

The news of his death became public only during the proceedings of a habeas corpus petition by Major Ishaq, a week after his death. The prosecution lawyer came up with a story that upon reading his mother’s letter which disclosed that his father had become mentally unstable, Hasan Nasir went into shock and later committed suicide. The sentry posted at the cell, the only non-CID employee, was never allowed to testify before the magistrate.

The facts of the case were brushed under the carpet, a veil of secrecy descended upon the case and completely stonewalled, Major Ishaq withdrew his petition.

Major Ishaq writes that the wording of the City Magistrate's post-mortem report that the mark of the noose around the neck of the body was below the collarbone disproves hanging and supports strangulation.

Hasan Nasir’s mother Zahra Alamdar Hussein, who lived in Hyderabad Deccan, learnt of her son’s murder and came to Lahore. She asked for a post mortem to be conducted – the military regime tried to block that too but the courts allowed it.

Ayub’s government then tried to conceal the location of Nasir’s grave. Finally, on orders of the court, it was located, a body was taken out and his mother was asked to identify her dead son. She refused to acknowledge that the exhumed body was that of her son. This shows that the police disposed of Hasan Nasir’s body surreptitiously so that their horrendous torture may never be discovered. His mother returned to Hyderabad Deccan without his body. An Inspector of the CID told the press that his mother had been asked by Indian communists to reject her son’s body. Even in the face of her grief, the brutal forces of the state did not give up on their agenda.

The regime put out a rumour that he was interred at Lahore’s famous Miani Sahab graveyard, although Major Ishaq’s own interviews with the yard’s grave diggers and the records of the graveyard yielded the fact that no body had been buried under police watch around the time of Hasan Nasir’s death.

(This article is retrieved from origional written by Saeed Shahid, published in The Friday Times 10 February 2011.)

Archived from the original

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0